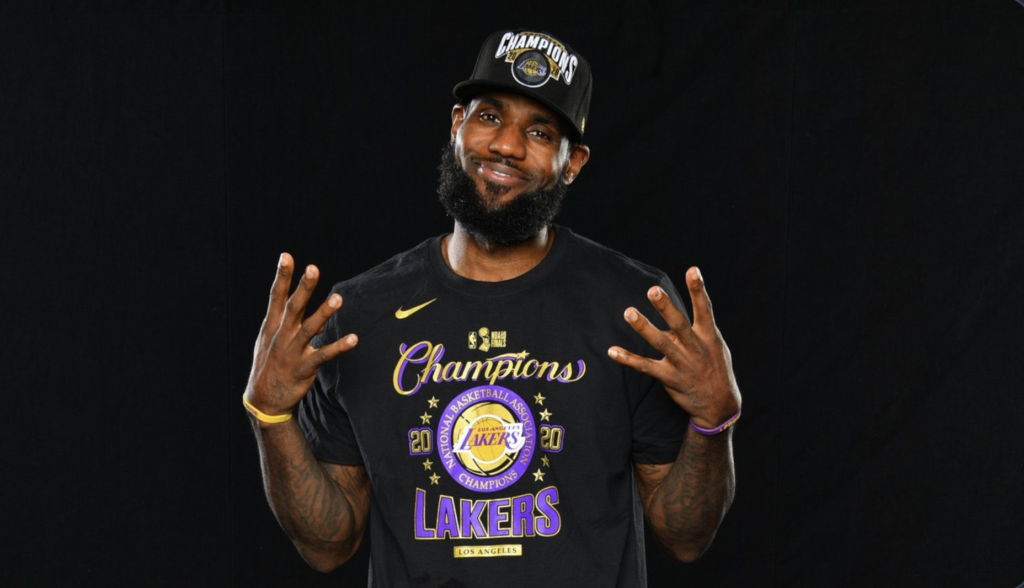

$100M Win For The King OFF The Court

25 Jun, 2020

“We’ve been through a lot this year,” said LeBron James. The three-time NBA champion and Los Angeles Laker talked to me on June 23 via Zoom with his childhood friend and business partner, Maverick Carter. It was the second of two joint interviews to discuss their new company, but the first since the world locked down because of Covid-19. James was in their hometown of Akron, while Carter was in L.A. Kobe Bryant’s death in January was followed by the pandemic and the suspension of the NBA season, and then, of course, the horrific killing of George Floyd. “Just seeing that video, how many people were hurt not only in Minneapolis, but all over the world—and especially in the Black community, because we’ve seen this over and over and over. So, you know,” he added, “it’s been a lot that’s gone on in 2020.”

The pair thought it was going to be a big year for different reasons. On March 11, the same day the NBA suspended its season and a little more than a week before their adopted hometown ordered residents to shelter in place, James and Carter formed the SpringHill Co. after raising $100 million. They describe it as a media company with an unapologetic agenda: a maker and distributor of all kinds of content that will give a voice to creators and consumers who’ve been pandered to, ignored, or underserved.

SpringHill is named for the Akron apartment complex where James and his mom moved when he was in sixth grade. It consolidates the Robot Co., a marketing agency, with two other businesses. The first, SpringHill Entertainment, is behind The Wall, a game show on NBC, and the movie Space Jam: A New Legacy, which stars James and is scheduled to be released next year. The second, Uninterrupted LLC, produces The Shop: Uninterrupted—an HBO talk show featuring James, Carter, and other Black A-list celebrities—as well as Kneading Dough, an online partnership with JPMorgan Chase & Co., in which athletes talk about money to promote financial literacy. (“They do it in a way that’s incredibly relatable,” says Kristin Lemkau, chief executive officer of JPMorgan’s U.S. wealth management business, who created the show with Carter.) Uninterrupted, a hybrid production-marketing business, is also responsible for a Nike Inc. shoe collaboration and a hoodie collection for Pride Month designed with soccer star Megan Rapinoe and basketball great Sue Bird.

In a February interview at the Lakers practice facility in El Segundo, they talked about SpringHill as a platform to give people of color the creative control that’s long eluded them. Carter calls the company a “house of brands.” It’s part Disney storytelling power, part Nike coolness, and part Patagonia social impact. In 2020 stories can be told in many different ways—on social media, in films, as well as with sneakers and sweatshirts. “This is ultimately a company that’s about point of view, the community you serve, and empowerment,” says L.A. investment banker Paul Wachter, who helped put the project together. “This is a company designed to move the culture.”

At the practice facility, a day after putting up 40 points on the New Orleans Pelicans, James told me: “When we talk about storytelling, we want to be able to hit home, to hit a lot of homes where they feel like they can be a part of that story. And they feel like, Oh, you know what? I can relate to that. It’s very organic to our upbringing.” Carter added: “When you grow up in a place like where we were, no matter how talented you are, if you don’t even know that other things exist, there’s no way for you to ever feel empowered because you’re like, I’m confined to this small world. That’s our duty. A lot of exposure.”

What was aspirational in February is a lot more real now. Black people are dying from the coronavirus at more than twice the rate of Whites, amid a recession in which Black unemployment has climbed to its highest level in more than a decade, and while an historic wave of protests is sweeping across the country—and world. But these are the times James and Carter find themselves in, and they may be the two people best suited to help others voice and answer the questions we’re all asking. Discussions about race dominate media. Books about White privilege and anti-racism top bestseller lists; U.S. demand for Netflix Inc.’s satirical Dear White People and When They See Us, a miniseries about the Central Park Five, skyrocketed as protests got under way, according to Parrot Analytics. HBO Max temporarily removed Gone With the Wind from its catalog (in honor of Juneteenth, HBO.com made The Watchmen available for free), while Epic Games Inc. got rid of police cars in Fortnite.

Carter took advantage of the lockdown to spend virtual one-on-one time with the 105 employees of the new venture, as well as to finalize partnerships. He signed a TV production deal with Walt Disney Co. and is working with Netflix on a basketball-themed movie that would star Adam Sandler. A series he worked on with Netflix, Self-Made, about Madam C.J. Walker, a Black woman who created a beauty empire in the early 20th century, starring Octavia Spencer, premiered in March.

As the pandemic ground Hollywood to a halt, SpringHill Entertainment joined with Laurene Powell Jobs’s XQ Institute to produce a virtual ceremony James hosted called Graduate Together: America Honors the High School Class of 2020. It featured addresses by former President Obama and Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai.

Carter said on Zoom, “I’m getting a lot of calls from other CEOs. A lot of calls on, ‘What are you doing? What do you think we should be doing?’ I’m explaining to people, ‘Don’t treat this as a moment,’ ” he said. This is bigger than a moment—the attention that issues of inequality are getting right now is “more like what this country should be, and what this world should be,” he said. “We’ve always been about empowering people who feel like us and come from the communities that we come from and want to believe in our mission.”

Devin Johnson, SpringHill’s chief operating officer, says that diversity is built into the company. He says its employees are 64% people of color and 40% female. “I’ve never had to convene a task force,” he says, as other companies scramble to figure out how they can be more reflective of society.

SpringHill might just sound like another superstar athlete’s vanity project. But Johnson says the company isn’t set up for—and around—a single athlete; rather, it’s a platform in his image: “You can’t create a real digital business on a celebrity. We don’t do that with LeBron. He is our founder and our North Star, but the business isn’t built on everything touching him.”

That attitude has freed up James for other projects—like, for example, playing professional basketball. Play is scheduled to resume on July 30, with 22 teams competing for spots in the playoffs, all to be held in a quarantine bubble at Walt Disney World in Orlando. Many have picked the Lakers to win the title.

And earlier this month, James recruited current NBA stars such as Trae Young of the Atlanta Hawks, as well as former star and now broadcaster Jalen Rose, to form More Than a Vote. The group is focused on protecting voter rights and preventing suppression, especially in Black communities. James announced it after social media posts showed people waiting for hours to cast ballots in Georgia’s primaries. “We’ve had voter suppression for so long,” James said on Zoom. “People not understanding how they can vote, where they can vote, if their vote really counts.”

After forming the group, James was criticized by Hong Kong democracy activist Joshua Wong, who accused him of being hypocritical. Wong said in a tweet that James’s position didn’t align with past comments. He was widely criticized last year for calling Houston Rockets General Manager Daryl Morey’s support for the city’s protesters “misinformed.”

In February, when I asked what he’d learned from that experience, James said it taught him to “keep an open mind about how to continue to get better.” On the June 23 call, James said: “I speak about things that I’m knowledgeable about, that I’m educated on. And at the end of the day, right is right, and wrong is wrong. I want the betterment of people—no matter skin color, no matter race, no matter anything.”

A little more than a decade ago, it might have seemed unlikely that James and Carter would amass a war chest of $100 million. The investors are financial services company Guggenheim Partners LLC, UC Investments, News Corp. heir Elisabeth Murdoch, and SC.Holdings, the investment fund run by entrepreneur Jason Stein. James is chairman of SpringHill, and Carter is CEO. Joining them on the board, in addition to Murdoch and Guggenheim’s Scott Minerd, are Serena Williams, Apollo Global Management co-founder Marc Rowan, Live Nation Entertainment Inc. CEO Michael Rapino, Boston Red Sox Chairman Tom Werner, and Wachter.

Carter was three years ahead of James at St. Vincent-St. Mary High School in Akron. When the Cleveland Cavaliers drafted James in 2003, Carter went to work at Nike full time. “Growing up, that was my favorite company, and I thought I loved it because of the shoes and sports,” Carter said in February. “In reality, they told me amazing stories about the athletes I cared about.”

He became James’s wingman in 2005. Their first major project, The Decision, was a failure. In a spectacle aired live on ESPN in July 2010, James announced—30 minutes in—that he was leaving Cleveland and signing a free-agent contract with the Miami Heat. “I’m gonna take my talents to South Beach,” he said. The theatrics didn’t sit well; Cleveland fans who felt betrayed burned his jersey. The sin was forgiven when he returned to the Cavs in 2014 and broke the city’s half-century championship drought two years later.

For many, the failure of The Decision validated suspicions that Carter was just another star athlete’s friend. But, Carter said, the fiasco helped him grow as a businessman. Even if their approach had been off, the importance of owning your own story, not just hawking someone else’s, wasn’t lost on Carter, or James—or on anyone else in the NBA, for that matter. What was underappreciated at the time was that The Decision ushered in an era of player empowerment that’s spread to other sports, as well as collegiate and high school athletics. There’s virtually no athlete who doesn’t feel emboldened to weigh in on just about anything on social media and demand a semblance of career control that would have been unheard of 20 years ago.

In 2014, Carter negotiated James’s deal with Nike, which ultimately will pay him more than $1 billion. Wachter, who’s advised Bono and Arnold Schwarzenegger, helped James and Carter team up with Cannondale bikes and Beats Electronics, a partnership that earned James more than $100 million when Apple Inc. bought Beats for $3 billion in 2014, say people familiar with the deal. And an arrangement to fold LRMR Marketing & Branding, the firm that still handles James’s endorsements, into Fenway Sports Management—owner of the Boston Red Sox, the New England Sports Network, and Liverpool Football Club—gave them equity in the English Premier League. “Through all of that, they’ve just said, ‘We’re going to do things our own way, and we’re going to write our own tickets,’ ” Wachter says. SpringHill, he adds, is “ultimately a manifestation of that.”

With those deals under way, Carter moved to L.A. in 2014 and turned his attention to media. He signed a production deal with Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. that gave James and him offices on the lot—on the fictional Wisteria Lane from Desperate Housewives, the satirical epitome of White suburban life.

Creating content that caters to the opposite of that is what Carter, James, and their backers want to do. UC Regents Chief Investment Officer Jagdeep Singh Bachher says: “This is not a time to slow down. This a time to double down on what they’re doing. There’s a need for leadership in the country, a need for examples that are inspiring for the country, and a need for content to mobilize the country in the right direction.”

James has cited Muhammad Ali as a role model. “Everyone was so fascinated about how great a boxer he was,” he said in February. “I think that was the least thing in his mind. Every day he was trying to figure out how to better the world. I think 80%, 90% of the people didn’t agree with anything that he did back when he was doing it. But that didn’t stop him. He stayed focused on his mission, and that’s what we’re talking about. The mission.”

On the Zoom call, James praised NBA Commissioner Adam Silver for encouraging players to speak up and for using “the NBA shield to back us.” When asked about the NFL’s treatment of Colin Kaepernick, the former San Francisco 49ers quarterback who took a knee during the national anthem to protest racial inequality and hasn’t played in the NFL since 2016, he said, “We have not heard that official apology to a man who basically sacrificed everything for the better of this world.” (NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell said in mid-June that he would “encourage” a team to sign Kaepernick.)

If there’s pressure on SpringHill to rise to the occasion, the founders are lucky that neither of them is new to expectations. James, after all, was on the cover of Sports Illustrated when he was a junior in high school. “I’m OK having that pressure of my community and other Black communities across America that look up to me and look to me for inspiration or for guidance,” he said in our last interview. “It’s just my responsibility, and I completely understand that. And so every day I leave my home, or I wake up out of my bed, I understand that it’s not just about me. I’m representing so many people.”

Bloomberg

Image LeBron James Instagram

Mentioned In This Post:

About the author

Related Posts

-

No Days Off For The King!

-

Tory Lanez Arrested For Shooting Megan Thee Stallion

-

This is Gonna Be Great!

-

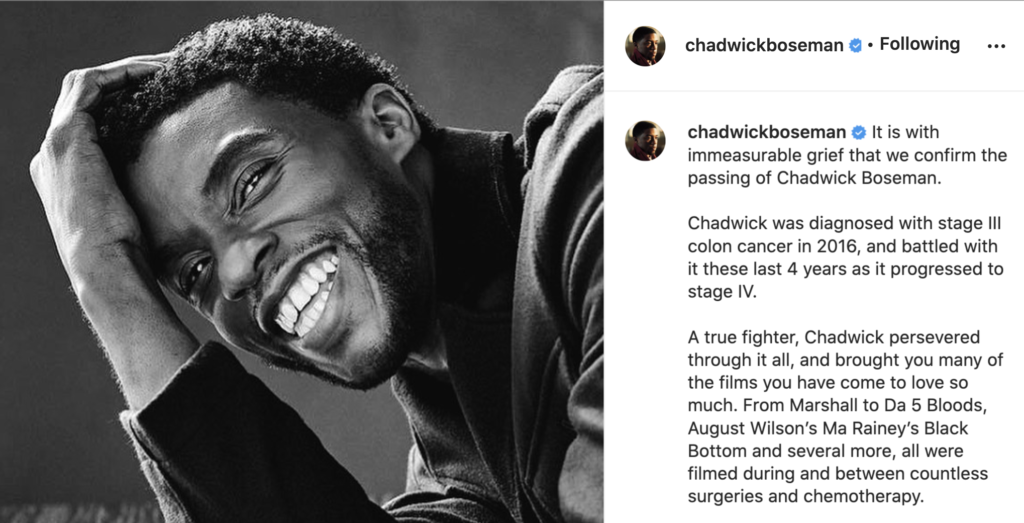

Rest Well King

-

Why We Love Lady Mae. Lynn Whitfield Dishes on the Greenleaf Family Matriarch

-

Star Actress Feared Dead

-

Broadway Star Loses Battle With Coronavirus

-

Jimmy Kimmel Finally Faces The Heat

-

Porn Star Charged With Sexual Assault

-

Seth Rogen is Not Going For Your Bullshit